|

|

| Tahlequah - Park Hill - Murrell Home & Ross Cemetery |

|

|

|

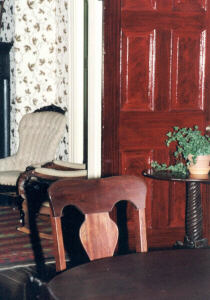

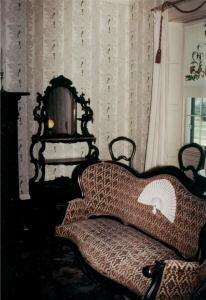

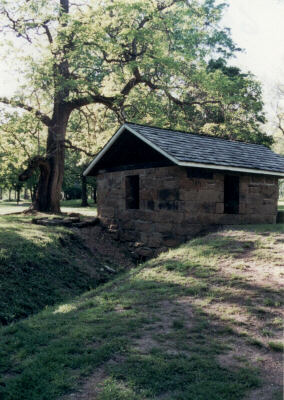

"Park Hill was the 'home base' for many Cherokees after coming from the East on the 'Trail of Tears.' The Cherokee National Female Seminary was built here. It was in Park Hill that Chief John Ross made his home, as well as his brother-in-law George Murrell, who's home still stands (pictured above and below). The Murrell Home, the Ross Cemetery, and the original Cherokee Female Seminary (now the location of the Cherokee Heritage Center) are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Park Hill was the home of the Park Hill Mission which had one of the earliest presses in Oklahoma, the Park Hill Publishing House." As I mentioned on the opening Tahlequah page, in 2001, we visited the Murrell Home and the Ross Cemetery here. |

|

|

|

|

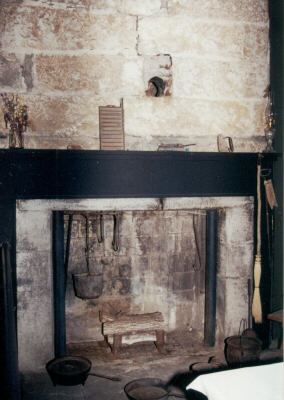

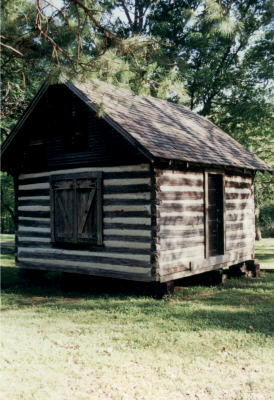

"Born in 1808 to a prominent family in Lynchburg, Virginia, George Michael Murrell moved to the Athens, Tennessee area as a young man to pursue mercantile interests with his brother and later his future father-in-law. There, in 1834, he met and married Minerva Ross. Minerva was the oldest daughter of Lewis and Fannie Ross, a wealthy and influential Cherokee family. Lewis Ross was a merchant, planter and treasurer of the Cherokee Nation. His brother, John, was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1828 until his death in 1866. When the Cherokees were forced to leave their homes in the East during 1838-39, Murrell chose to move with his wife's family to the new Nation in the west. In Park Hill, he established a plantation and about 1845, built a large frame home similar to those he remembered in Virginia. He called the house 'Hunterís Home' because of his fondness for the fox hunt. A rock building was added beside the creek branch over a cold spring to preserve food. Outbuildings included a barn with stables for his horses. Buildings probably added were a smokehouse, grist mill, blacksmith shop, corn cribs, and small cabins for slaves and employees. Murrell and his father-in-law also established a mercantile business in Park Hill, later moving it into Tahlequah. In 1855 Minerva Murrell died (likely of malaria). She was buried in the nearby Ross family cemetery. The Murrells had no children, but in 1851, three of Minerva's young cousins were living with them. Joshua and Jennie P. Ross were educated by the Murrells and remained close to them throughout their lives. In 1857 George married Minervaís youngest sister, Amanda. They had six children. Their first child died as an infant. The second, however, was born in their home in Park Hill in 1861. He was only ten months old when his parents left during the Civil War. George Murrell, a Virginian, supported the Confederates. However, as an intermarried Ross family member, he could never support the Cherokee Confederates, led by General Stand Watie, who were against the Ross family. He moved his family to nearby Arkansas and then to Virginia. George enlisted there, was commissioned as a major, and was stationed in a support role at the Confederate capitol in Richmond. Amanda, asked some of her family to occupy the home in her absence and they endured several of Watie's raids." |

|

|

||

|

|

"Mary Jane Ross,

a sister of Minerva and Amanda's wrote to her son Willie about the condition

of the Murrell home during the Civil War on October 2, 1865 . . .

(this photo of the "General Stand Watie" carving was taken in Tahlequah) |

|

|

|

"Although George and Amanda did come back to visit their old home after the War, they never made it their residence again. The area was devastated from repeated raids. Most of the homes and other buildings were badly damaged or destroyed by local partisans. Various members of Amandaís large extended family lived in the home during the War and through the rest of the 19th century. When the home was allotted to one of Amandaís relatives in 1906, the furnishings, which had remained in the house through the years, were shipped to descendants living in Louisiana. |

|

|

|

During the mid-1850s Murrell had inherited a large sugar plantation called 'Tally Ho' near Baton Rouge, La. Here he established a winter home. 'Hunterís Home' became the retreat from the Louisiana summers, a chance to visit relatives and check up on business interests. After the War, he continued to expand 'Tally Ho' plantation. He also acquired a large farm called 'Tate Springs' near Lynchburg, Virginia where he built a summer mansion. George and Amanda both died in the 1890s in Louisiana but are buried back in Lynchburg, Virginia. Though the home at Park Hill was looted during the war, the house survived. Most other homes were destroyed. 'Rose Cottage' (John Ross' home) and other notable structures were burned to the ground. |

|

In 1948, the State of Oklahoma bought the Murrell Home so that it could be preserved for future generations to enjoy. Jennie (Ross) Cobb, a great-granddaughter of Chief John Ross, is responsible for how the mansion looks today. She had lived in the Murrell home as a teen in the 1890s and knew the location of many of the original furnishings. She gathered the old furniture back to the house and took pictures of the inside. The photos were used by researchers to aide in the restoration work. The Murrell Home stands alone as a tribute to the antebellum era of the Cherokee Nation. Today, it is the only remaining antebellum plantation home in Oklahoma." |

|

|

|

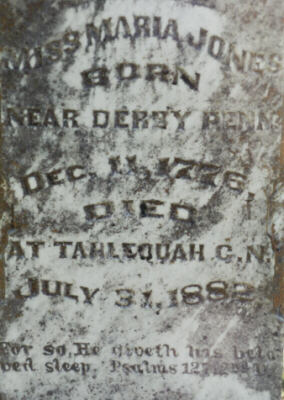

The above picture of John Ross and his wife hangs in the Murrell home. As mentioned above, and numerous other places throughout my wsharing Cherokee pages, John Ross was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1828 until his death in 1866. He was Chief during the Trail of Tears, the strife of resettlement in Indian Territory, and the stresses of the U.S. Civil War. The War Between The States reinforced divisions within the Cherokee Nation. John Ross wanted to remain neutral, and honor the treaties and agreements we had with the United States government. Stand Watie ultimately became a General for the Confederates. Old animosities found new expression throughout the Cherokee Nation. "John Ross' term as Chief was the most turbulent and conflict-ridden period in the Cherokee Nation's history, but he remained steadfast to the people, and fought to keep the nation united." He died in Washington D.C. following the end of the U.S. Civil War. I took the below photos during our visit to the Ross family cemetery. Miss Maria Jones is not somebody I know anything about. I took the picture of her headstone because of the dates and locations. Born in Pennsylvania at the start of the American Revolution, she lived until 1882, over 100 years. Imagine the changes she saw in her lifetime. Also, since 1882 was prior to Oklahoma statehood, notice that the location of her death is Tahlequah, C.N. (Cherokee Nation). |

|

|

|

|

"Also interred in this cemetery are numerous high-ranking leaders of the Cherokee Nation, members of the Murrell family, members of the Ross family and several survivors from the Cherokee Trail of Tears relocation. The cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002." This wraps up the Tahlequah Scrapbook Photos pages. It has taken over two months of fairly steady work to bring these pages together. Finishing at the cemetery causes me to reflect about my own journey. I am supposedly seven generations from our family's Cherokee heritage connection. The Cherokee do not have a blood quantum requirement. You must simply be able to trace your genealogy to someone listed on the Dawes Roll. I once tried spending an afternoon at the State of Michigan Library, starting the process, but I do not have the patience for such things, so I am not "officially" Cherokee anything. |

|

|

|

Then, why do I do all this? Why has the Cherokee connection become such a big part of my life? Both of my grandfathers were Irish Americans. The Irish in me finds a fair amount of expression, but nowhere close to the Cherokee. It is some solace, that even John Ross, by white standards, was only a small part Cherokee. By blood quantum, he was more of Scottish origin. Some of my friends, who are strongly connected to their indigenous roots, identify themselves first and foremost by their tribe. If someone asks if I am Cherokee, I will answer, yes. It took some real soul searching for me to arrive at this answer several years ago. Spiritual, emotionally, I feel it as my story. But, if pressed beyond being just "william" or a child of God, I see myself as simply American. I see my Cherokee heritage as an American story, even more so than the Irish (or German, or French). As Americans, with or without indigenous bloodlines, we were born upon this same piece of earth as my Cherokee ancestors. We need to respect that. We need to understand their story is an American story, not just a Cherokee story. When we begin to do so, with honest respect and humility, I believe we will find many of the answers we long for. |

|

Over the couple of months it has taken me to create these Tahlequah pages, I have been reading the book "every day is a good day" (Fulcrum Publishing) by Wilma Mankiller. The book is full of reflections by contemporary indigenous women. I finished it the same night I finished the museum page. Toward the end there was this quote from Ella Mulford, a Navajo biologist. "To restore balance in our communities, I believe that our philosophies, practices, and protocols that have been around since life began must survive. Our traditional stories include many lessons that were learned by our ancestors. By respecting our stories, we may be able to avoid similar hardships that come with the lessons. I believe our generation today does not consider indigenous knowledge as significant, important, worthy, and of value to our present way of life. Many of us are forgetting some very simple principles that are important to our survival. We are losing our belief in our way of life. Some of the things we are forgetting are that we are a part of something bigger, and that we are a continuation of our ancestors. Not only are we connected in the physical to all things in the present, but we are also connected to our past and future. We need to bring our indigenous knowledge forward as a means for our survival. This does not mean we go back to living like we did in the past, it means we bring forward our ancestors' way of thought and actions. We must change our way of thought and actions if we are going to survive." |

|

I am not entirely sure the way it is worded, but it is quite possible, her quote was directed at and intended for the Navajo, or generic indigenous community. I think it is, or should be, a message to and for Americans . . . all Americans. Maybe that is why I do this . . . I do not really know. |

|

Text shown in quotation marks throughout these pages comes from various brochures, pamphlets, information sheets, other items picked up on our visits, Cherokee Heritage Center assistance, and Internet searches. Find many sources in the links pages. |

|

|